My latest article on Impakter, updated 24 February 2019 with the news that Salvini is taking funds from Russia. Here is the opening:

Italy has a surprising weakness for populism à la Trump. It began over twenty-five years ago with Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia party and is still going strong with the extreme-right populist Lega leader Matteo Salvini. Berlusconi and Salvini share the same worldview with Trump: a visceral attachment to national sovereignty (my country first!), a rejection of multilateralism and international cooperation in any form, and a determined anti-immigration and pro-business stance.

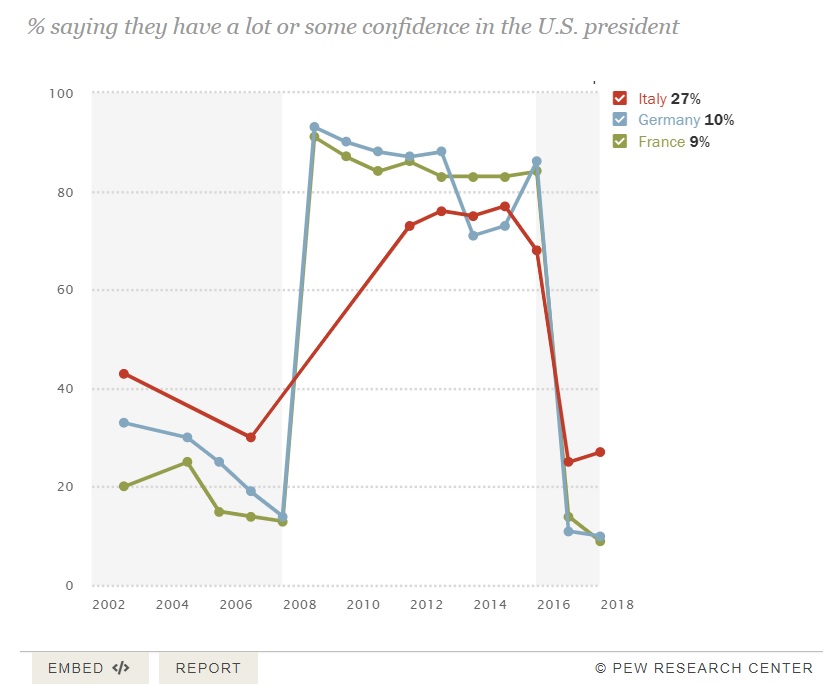

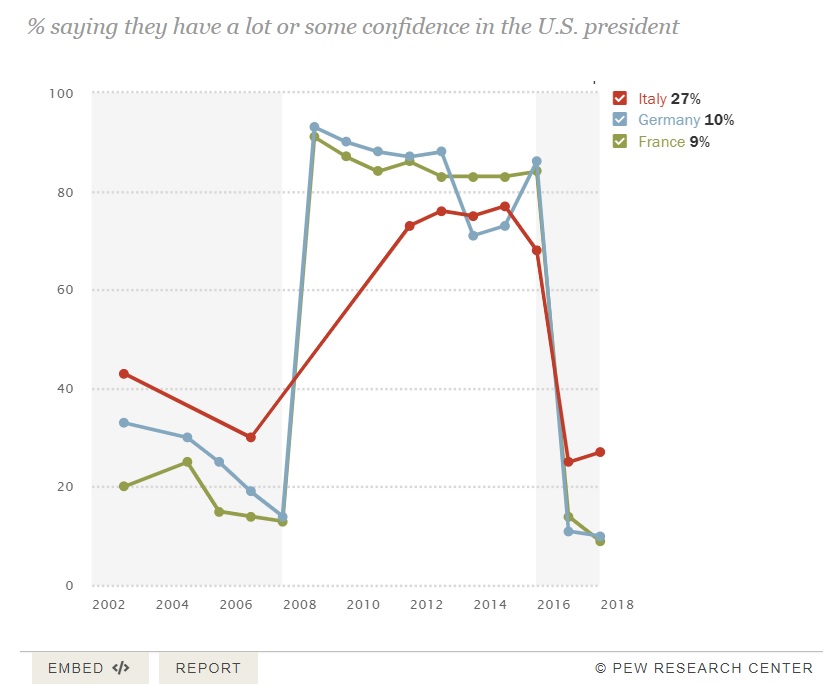

As to the Italian fascination with Trump, it is unique in the group of advanced, politically mature European countries that constitute the core of the European Union. Compared to fellow citizens in Spain, France and Germany, Italians are three to four times as likely to have “a lot or some confidence in the U.S. President”, as shown by a recent Pew Research Center survey (October 2018):

Trump does slightly better in the UK (28%), no doubt as a result of Brexit and Britain’s continuing “special friendship” with the United States. And, predictably, he does best in Europe’s most “illiberal democracies”: Poland (35%) and Hungary (31%).

Admittedly, Italy’s fatal attraction for strongmen is nothing new. Setting aside Mussolini and fascism and turning to modern times, we have Silvio Berlusconi, the TV mogul. Berlusconi has shaped Italian politics, opening the door to extreme right parties that were once banned because of their fascist roots. To understand how it happened and see where Salvini’s populism could lead Italy, it helps to look at his legacy.

The start was even more explosive than Macron’s. Founded in December 1993, the party quickly gained a relative majority and won general elections three months later. That was the result of a skillful use of media campaign techniques on Berlusconi’s Mediaset, a near monopoly in commercial TV. The party’s earliest officials were Publitalia executives, the advertising arm of his business empire.

Forza Italia always was - and still is - Berlusconi’s “personal party”. And he proceeded to lord it over Italy, both as the head of the center-right coalition and serving as Prime Minister for a total of nine years. Considered the most influential politician since Mussolini, there is no question that he has shaped Italy’s politics and economy over two decades - unfortunately leaving the economy in shambles.

Yet he had vowed he would make his compatriots rich. Many believed him, seeing how rich he was himself. But Italy’s economic growth rate remained abysmal throughout. In 2010, only Haiti and Zimbabwe fared worse than Italy. Likewise, he couldn’t deliver on his promise to reform the slow and inefficient justice system, as his efforts at reform turned out to be personal moves to defend himself and his assets from prosecution. As to immigration, he was the first politician to tighten immigration rules in Italy and establish a special relationship with Libya to discourage inflows of migrants across the Mediterranean.

The most damaging result of the Berlusconi years was the return in mainstream politics of extreme right anti-establishment political parties, brought in and rehabilitated as Forza Italia’s partners: Umberto Bossi’s Lega (then called Lega Nord as it was both anti-Rome and anti-Southern Italy) and Gianfranco Fini’s National Alliance with deep roots in fascism.

2011, the height of the Euro crisis, was a turning point. In April, Berlusconi was put on trial, accused of paying an underage prostitute. By November, he was forced out of office. He left Italy in financial disarray, with an estimated debt of €1.9 trillion. He always claimed it was a “EU plot” by Brussels bureaucrats.

On 1 August 2013, he was convicted of tax fraud, banned from office and condemned to four years in jail that were commuted to “community service” due to his age (he was 77). In November of that year, the Senate expelled him from Parliament and he vowed to follow the example of Beppe Grillo, the comedian and founder of the 5 Star Movement, who was able to lead his party in spite of not being a member of Parliament Grillo has made it a principle in his party that anyone with a criminal conviction cannot hold a public office - himself included, since he was convicted of manslaughter in a car accident in 1981.

Today, at 82, Berlusconi is still in politics. Forza Italia has lost its luster and the Lega, that used to be his junior partner, is well ahead in the polls.

Yet the last ten days had been a turning point for Salvini with several wins. On 10 February, his party, the Lega, came first in local elections in the Abruzzo region, with 27,4% - a number oddly close to the one in the above-mentioned Pew survey rating Trump, suggesting that this could be indicative of the core support for any populist in Italy.

...

The rest on Impakter, click here.

Italy has a surprising weakness for populism à la Trump. It began over twenty-five years ago with Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia party and is still going strong with the extreme-right populist Lega leader Matteo Salvini. Berlusconi and Salvini share the same worldview with Trump: a visceral attachment to national sovereignty (my country first!), a rejection of multilateralism and international cooperation in any form, and a determined anti-immigration and pro-business stance.

As to the Italian fascination with Trump, it is unique in the group of advanced, politically mature European countries that constitute the core of the European Union. Compared to fellow citizens in Spain, France and Germany, Italians are three to four times as likely to have “a lot or some confidence in the U.S. President”, as shown by a recent Pew Research Center survey (October 2018):

Trump does slightly better in the UK (28%), no doubt as a result of Brexit and Britain’s continuing “special friendship” with the United States. And, predictably, he does best in Europe’s most “illiberal democracies”: Poland (35%) and Hungary (31%).

Admittedly, Italy’s fatal attraction for strongmen is nothing new. Setting aside Mussolini and fascism and turning to modern times, we have Silvio Berlusconi, the TV mogul. Berlusconi has shaped Italian politics, opening the door to extreme right parties that were once banned because of their fascist roots. To understand how it happened and see where Salvini’s populism could lead Italy, it helps to look at his legacy.

Berlusconi’s Legacy: A Brilliant Start, Broken Promises and a Humiliating End

Much as Macron did with his party “La République En Marche”, Berlusconi created a party literally overnight, Forza Italia (“Go Italy” - note the nationalistic touch and the reference to Italy’s passion for football).The start was even more explosive than Macron’s. Founded in December 1993, the party quickly gained a relative majority and won general elections three months later. That was the result of a skillful use of media campaign techniques on Berlusconi’s Mediaset, a near monopoly in commercial TV. The party’s earliest officials were Publitalia executives, the advertising arm of his business empire.

Forza Italia always was - and still is - Berlusconi’s “personal party”. And he proceeded to lord it over Italy, both as the head of the center-right coalition and serving as Prime Minister for a total of nine years. Considered the most influential politician since Mussolini, there is no question that he has shaped Italy’s politics and economy over two decades - unfortunately leaving the economy in shambles.

Yet he had vowed he would make his compatriots rich. Many believed him, seeing how rich he was himself. But Italy’s economic growth rate remained abysmal throughout. In 2010, only Haiti and Zimbabwe fared worse than Italy. Likewise, he couldn’t deliver on his promise to reform the slow and inefficient justice system, as his efforts at reform turned out to be personal moves to defend himself and his assets from prosecution. As to immigration, he was the first politician to tighten immigration rules in Italy and establish a special relationship with Libya to discourage inflows of migrants across the Mediterranean.

The most damaging result of the Berlusconi years was the return in mainstream politics of extreme right anti-establishment political parties, brought in and rehabilitated as Forza Italia’s partners: Umberto Bossi’s Lega (then called Lega Nord as it was both anti-Rome and anti-Southern Italy) and Gianfranco Fini’s National Alliance with deep roots in fascism.

2011, the height of the Euro crisis, was a turning point. In April, Berlusconi was put on trial, accused of paying an underage prostitute. By November, he was forced out of office. He left Italy in financial disarray, with an estimated debt of €1.9 trillion. He always claimed it was a “EU plot” by Brussels bureaucrats.

On 1 August 2013, he was convicted of tax fraud, banned from office and condemned to four years in jail that were commuted to “community service” due to his age (he was 77). In November of that year, the Senate expelled him from Parliament and he vowed to follow the example of Beppe Grillo, the comedian and founder of the 5 Star Movement, who was able to lead his party in spite of not being a member of Parliament Grillo has made it a principle in his party that anyone with a criminal conviction cannot hold a public office - himself included, since he was convicted of manslaughter in a car accident in 1981.

Today, at 82, Berlusconi is still in politics. Forza Italia has lost its luster and the Lega, that used to be his junior partner, is well ahead in the polls.

In the photo: Salvini and Berlusconi. That day, 7 January 2018, Berlusconi, Salvini and Meloni, the leader of Fratelli d’Italia, agreed on the distribution of electoral colleges Source: La Stampa, photo LaPresse

Is Salvini, Berlusconi’s heir, Italy’s Trump?

On 21 February, the Italian newspaper L'Espresso published shocking news: That Salvini's party the Lega is likely to be secretly financed by Putin, to the tune of €3 million, with the goal of giving it a boost in the upcoming European Parliament elections and more generally spread discontent in Europe. This is of course not the first time that news emerge of Russian funding extreme-right, anti-establishment populist parties with the purpose of destabilizing Europe - notably Marine Le Pen in France is said to have received some €11 million from her friend Putin.Yet the last ten days had been a turning point for Salvini with several wins. On 10 February, his party, the Lega, came first in local elections in the Abruzzo region, with 27,4% - a number oddly close to the one in the above-mentioned Pew survey rating Trump, suggesting that this could be indicative of the core support for any populist in Italy.

...

The rest on Impakter, click here.

Comments